Search Great War Images from the U of S

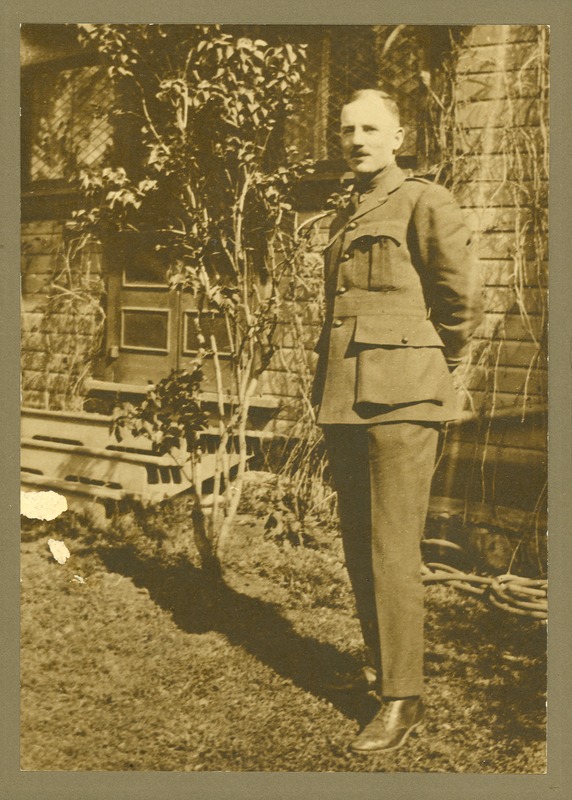

Major Reginald Bateman

"We hear much, perhaps too much, at the present time of the horrors of war; I wish to-day to speak of its blessings." So began Reginald Bateman's address to the University YMCA on a Sunday afternoon in October, 1914. Bateman, one of the original four faculty members and the first professor of English, had come to Saskatoon in 1909 from Ireland. He had just completed his academic training at Trinity College, Dublin. His speech to the YMCA was given on the eve of his departure to the European war, where he would lose his life and in the process become a University hero.

"We hear much, perhaps too much, at the present time of the horrors of war; I wish to-day to speak of its blessings." So began Reginald Bateman's address to the University YMCA on a Sunday afternoon in October, 1914. Bateman, one of the original four faculty members and the first professor of English, had come to Saskatoon in 1909 from Ireland. He had just completed his academic training at Trinity College, Dublin. His speech to the YMCA was given on the eve of his departure to the European war, where he would lose his life and in the process become a University hero.

Like most in 1914, Bateman was eager to enter the fray. He was not just seeking adventure, however, but believed he was taking part in something that was necessary for human progress. He was clearly influenced by Social Darwinism: "Biologically, struggle and self-sacrifice by one generation on behalf of the next are the conditions of the perpetuation of the species. History teaches that once a nation ceases to struggle or to be prepared to struggle for its existence, once it loses its military spirit and the willingness to fight to the death, if need be, for its national honour, its greatness invariably declines, and its growth ceases." For Bateman, war was "the climax of human endeavor" and "the only entirely adequate test of a nation's spiritual quality." Failure in war was the result of a decay of "national morality" and success an "indication of national virtue." A healthy national morality combined asceticism, moral sternness, and national service: "Self-sacrifice, self-denial, temperance, hardihood, discipline, obedience, order, method, organizing power, intelligence, purity of public life, chastity, industry, resolution are some only of the national and individual attributes which go towards producing the efficiency of modern armaments." The young professor urged his listeners not to neglect the spiritual dimension of war. Granted, the physical aspects of armed conflict were grim. But he argued, "a past unstained by the blood of human strife would be more dreadful still." War should be seen as a "purifier which purges the corruption of a too-long-continued peace, and which saves nation and individual alike from sloth and selfishness."

Bateman served on the Western Front three times. To return the third time, he even accepted a reduction in rank, from major to lieutenant, and was killed on 3 September 1918. Unlike most who experienced the trenches, his ardor for war never seems to have diminished. Awaiting his third trip to France, Bateman indicated to a colleague that he wished he had never left the front: "If I had stayed on, I should have got my commission and should have valued it much more than the one I actually did get. I might have been killed, but I was prepared for that, and I think there is no better way a man can die. It is comparatively seldom in the world's history that a man gets a chance to die splendidly. Most deaths are somewhat inglorious endings to not very glorious careers. A war like the present gives a man a chance to cancel at one stroke all the pettiness of his life.

The material presented here (above link) includes excerpts from Reginald Bateman, teacher and soldier / A memorial volume of selections from his lectures and other writings (Bateman Papers, MG 5) and correspondence from and addresses by Bateman (J.E. Murray Papers, MG 61).