Search Great War Images from the U of S

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan limped into the Great War. The great boom years of the early twentieth century gave way to a recession in 1912 that ate away at the economy. Western Canada was particularly hard hit. Grain prices plummeted. The real estate market, and with it the construction industry, collapsed. And the two new, uncompleted transcontinental railways (Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Pacific) sustained mortal blows from which they never recovered. There was even drought in some southern districts.

Saskatchewan limped into the Great War. The great boom years of the early twentieth century gave way to a recession in 1912 that ate away at the economy. Western Canada was particularly hard hit. Grain prices plummeted. The real estate market, and with it the construction industry, collapsed. And the two new, uncompleted transcontinental railways (Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Pacific) sustained mortal blows from which they never recovered. There was even drought in some southern districts.

Badly staggered by the recession that had hobbled the provincial economy, places like Moose Jaw, Prince Albert, Regina, and Saskatoon looked to the war to stop the slide into financial ruin. The most urgent problem was mounting debt, a legacy of the boom years that threatened to swallow up the communities and any lingering hopes for urban greatness. Cities had not only recklessly spent millions of dollars on facilities and infrastructure they would not need for the foreseeable future, but they had blithely borrowed the money to fund this development based on totally unrealistic local assessment values. The collapse of the boom left cities scrambling to avoid default. Regina's debenture debt in 1913 was over four million dollars. The ever-ambitious Saskatoon was on the hook for nearly twice that much--an incredible 7.6 million. The pre-war recession left its imprint of the urban landscape. In Regina, work on the Chateau Qu’Appelle, a luxury Grand Trunk Pacific hotel near Wascana Park, was suspended. The steel framework stood for more than a decade, a rusting reminder of what might have been, before it was dismantled. Construction also came to an abrupt end on the La Colle Falls hydroelectric project outside Prince Albert with the dam less than half-way across the North Saskatchewan River. Not only was the city eventually forced to declare bankruptcy in 1918--the first city in Saskatchewan to default on its debt--but it did not finish paying for the project until 1965.

Farming was also hurting before the war. A recession-induced drop in grain prices had translated into the first ever decline in major crop acreage in 1914. A severe drought in the southwestern part of the province only aggravated the already dismal outlook. This region, with its light soils and scanty precipitation, had always been considered too arid for cultivation. But during the frenzied years of the great settlement boom, the federal government had amended the Dominion Lands Act in 1908 to allow homesteading in ranching country; prospective settlers could file for 160 acres of homestead land and buy an adjoining preemption of the same size at three dollars per acre. These larger farms were supposed to make up for the deficiencies of the soil, and land-hungry immigrants, mostly from the United States, poured in by the thousands. By 1910, there were elevators, towns, and wheat fields where there had been none only two years earlier. But then the doubts began to set in when the broken land started to drift in the drying winds. Indeed, the need to rethink land policy in the area was driven home during the summer of 1914 when crops failed, in some places for the third consecutive year. The situation was so desperate that the provincial government had to provide relief to destitute farmers.

The coming of war was expected to revive the sagging economy and generate a new round of province-building.

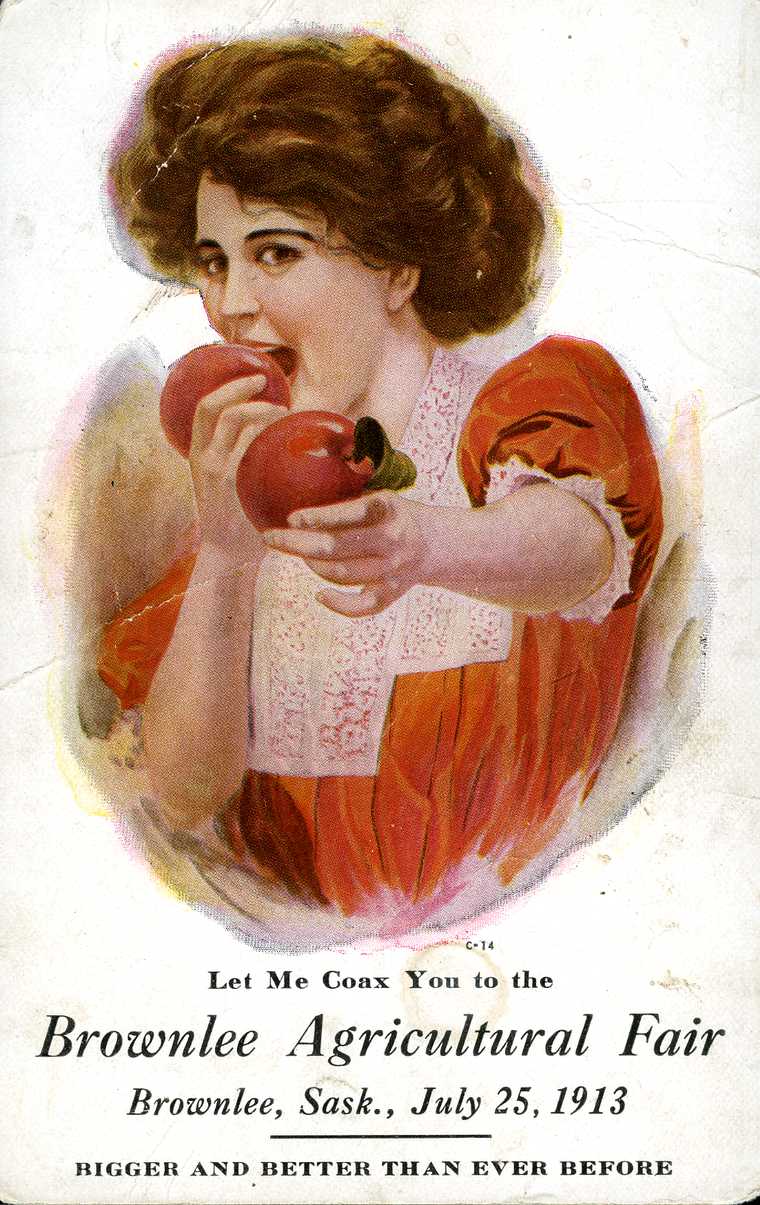

The materials scanned for this section were taken from the Shortt Library and Pamphlet Collection of the University Archives and Special Collections.