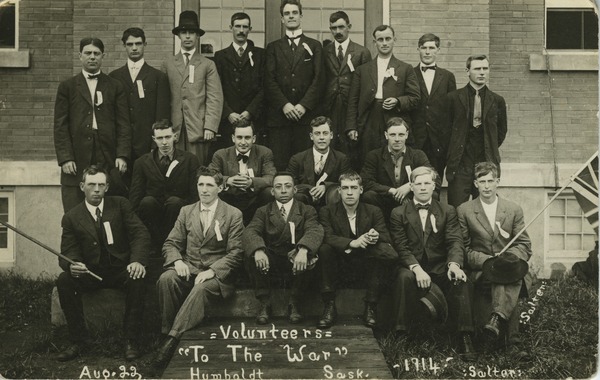

Search Great War Images from the U of S

Recruitment

Walter Murray, the President of the University of Saskatchewan, was an active imperialist and a zealous supporter of the war. He “plunged into” leading a recruiting campaign in Saskatoon, encouraging the members of the University “staff and students to offer their services” and promising educational benefits to students and financial inducements to faculty and the wives of those who enlisted. He played a dominant role in the formation of the Western Universities Battalion and almost single-handedly recruited the Saskatchewan Company for the Battalion. By early 1915, he had directed the University Senate to impose compulsory physical drill, including military drill, for all students. His biographers argue convincingly that Murray romanticized war, viewing Saskatchewan’s enlisted men as “young knights going off to do battle for the Empire.” Murray’s success as a recruiter may be seen in the decision in November 1914 of Arthur Grunchy. The Editor of The Sheaf at the University of Saskatchewan, Grunchy announced in an editorial that he had just enlisted, claiming that Canada was fighting not only for herself but also for “civilization,” because Germany and also Austria-Hungary loomed as a “threat” to the country’s “most cherished principles.” Yet The Sheaf reproved the “Viking-like thirst for glory” of Professor Reginald Bateman of English who deserted his classes in mid-term, leaving his students to unprepared substitutes. This emphasis on fighting for “civilization,” for “cherished institutions,” anticipated the growing national theme of a “war for democracy.”

Walter Murray, the President of the University of Saskatchewan, was an active imperialist and a zealous supporter of the war. He “plunged into” leading a recruiting campaign in Saskatoon, encouraging the members of the University “staff and students to offer their services” and promising educational benefits to students and financial inducements to faculty and the wives of those who enlisted. He played a dominant role in the formation of the Western Universities Battalion and almost single-handedly recruited the Saskatchewan Company for the Battalion. By early 1915, he had directed the University Senate to impose compulsory physical drill, including military drill, for all students. His biographers argue convincingly that Murray romanticized war, viewing Saskatchewan’s enlisted men as “young knights going off to do battle for the Empire.” Murray’s success as a recruiter may be seen in the decision in November 1914 of Arthur Grunchy. The Editor of The Sheaf at the University of Saskatchewan, Grunchy announced in an editorial that he had just enlisted, claiming that Canada was fighting not only for herself but also for “civilization,” because Germany and also Austria-Hungary loomed as a “threat” to the country’s “most cherished principles.” Yet The Sheaf reproved the “Viking-like thirst for glory” of Professor Reginald Bateman of English who deserted his classes in mid-term, leaving his students to unprepared substitutes. This emphasis on fighting for “civilization,” for “cherished institutions,” anticipated the growing national theme of a “war for democracy.”

Murray’s activities as a recruiter illustrate the nature of recruiting throughout Canada, at least until conscription was introduced in 1917. The recruiting was local, not centralized, and often conducted by well-placed leaders of the militia, hundreds of clergymen, patriotic mayors who reflected “Edwardian civic pride,” and other men from the local elites who came primarily from the professional middle class and upper class. The campaign was also mostly civilian-driven, although soldiers on leave or permanently disabled by wounds also participated. Working class men were employed often immediately after their enlistment by being designated as “Recruiting Sergeants” to call upon, cajole or persuade others of their world to enlist. Recruiters used posters, often taken from the British, and distributed by the hundreds of thousands. Probably the most frequently deployed poster was that of Lord Kitchener, England’s Secretary of State for War, with his by now notorious words, “The Empire Needs You,” coupled with his forbidding countenance and his finger pointing directly to anyone viewing his visage. After propaganda about alleged German atrocities in Belgium against Nuns and other women reached Canada, recruiters developed another dominant poster theme that called upon men to enlist so as to protect women. Such themes were prominent at the rallies that were staged in arenas, sometimes in factories or in other work places. Sometimes recruiters even knocked on the doors of prospective recruits at home. Bands played at rallies, the idea of war as sport was frequently emphasized and picnics were scenes for recruiting. Whatever the venue, the recruiters consistently relied on “imperial sentiments and symbols” that reflected themes deeply resonant with prewar “cultural and intellectual attitudes.” And the corollary of this “Imperial” appeal was “the theme of Canadian nationalism.”

Murray’s ideas, expressed in high diction, as well as his patriotic actions reflect in microcosm the thoughts and behaviour of many other Canadians of his standing. His romantic view of war, his emphasis on “chivalry” reveal graphically the degree that he and so many other recruiters relied, probably unconsciously, upon a spirit and impulses that were “anti-modern” or deeply traditional. Like most of his contemporaries, Murray was a Victorian Canadian and, as such, believed in the “objective good” of the British Empire. In the conflict that was the first “modern” war, recruiting votaries, such as Murray, relied upon religious themes, the cult of “sportsmanship,” and stereotyped gender ideals. While “manliness” was underscored for recruits, femininity was demanded of women. They were encouraged to call upon men to enlist, while as females their lives were to be dedicated to preserving, as moral guardians, the sanctity of the family. Canadians were exhorted to cast aside the “corrupting materialism” of contemporary society and seek “transcendence” in a higher cause through embracing the call to duty. Enlistment meant comradeship, commitment, exercise and fresh air as opposed to the staleness of modern industrial life. E.H. Oliver, Historian and Principal of St. Andrew's College, the Presbyterian Theological College at the University of Saskatchewan, particularly emphasized the Christian dimension of the Canadian Soldiers role. In a sermon in 1916, Oliver piously claimed that “the human race is marching to its Calvary,” thereby, in his mind, offering soldiers in the trenches an explanation transcending appeals to “traditional patriotism,” and ideas of “history as a benign process.” He linked the troops’ sacrifice to the redeeming death of Christ. Murray earlier had arranged for Oliver to be designated Chaplain of the Western Universities Battalion.