Search Great War Images from the U of S

Enemy Aliens

When Canada went to war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire in August 1914, unwelcome foreigners were turned overnight into “enemy aliens.” The majority of these people were unskilled Ukrainian labourers who had been brought to Canada in increasingly large numbers in the early twentieth century to work on the railways and other construction projects. This labor force generated little public interest or concern, especially since the men lived on the margins of the Canadian society. Indeed, in the opening months of the war, Ottawa initially called for public restraint in dealing with these immigrants from enemy countries and introduced a registration policy. But as hundreds of displaced enemy alien workers began to drift into Canadian cities in search of relief, Anglo-Canadians grew alarmed about the presence of these destitute men in their midst and demanded more drastic action. In the end, the federal government eventually bowed to public pressure and established a national network of internment camps. Over 8000 individuals, including women and children, would eventually be held in some dozen stations and camps across the country.

When Canada went to war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire in August 1914, unwelcome foreigners were turned overnight into “enemy aliens.” The majority of these people were unskilled Ukrainian labourers who had been brought to Canada in increasingly large numbers in the early twentieth century to work on the railways and other construction projects. This labor force generated little public interest or concern, especially since the men lived on the margins of the Canadian society. Indeed, in the opening months of the war, Ottawa initially called for public restraint in dealing with these immigrants from enemy countries and introduced a registration policy. But as hundreds of displaced enemy alien workers began to drift into Canadian cities in search of relief, Anglo-Canadians grew alarmed about the presence of these destitute men in their midst and demanded more drastic action. In the end, the federal government eventually bowed to public pressure and established a national network of internment camps. Over 8000 individuals, including women and children, would eventually be held in some dozen stations and camps across the country.

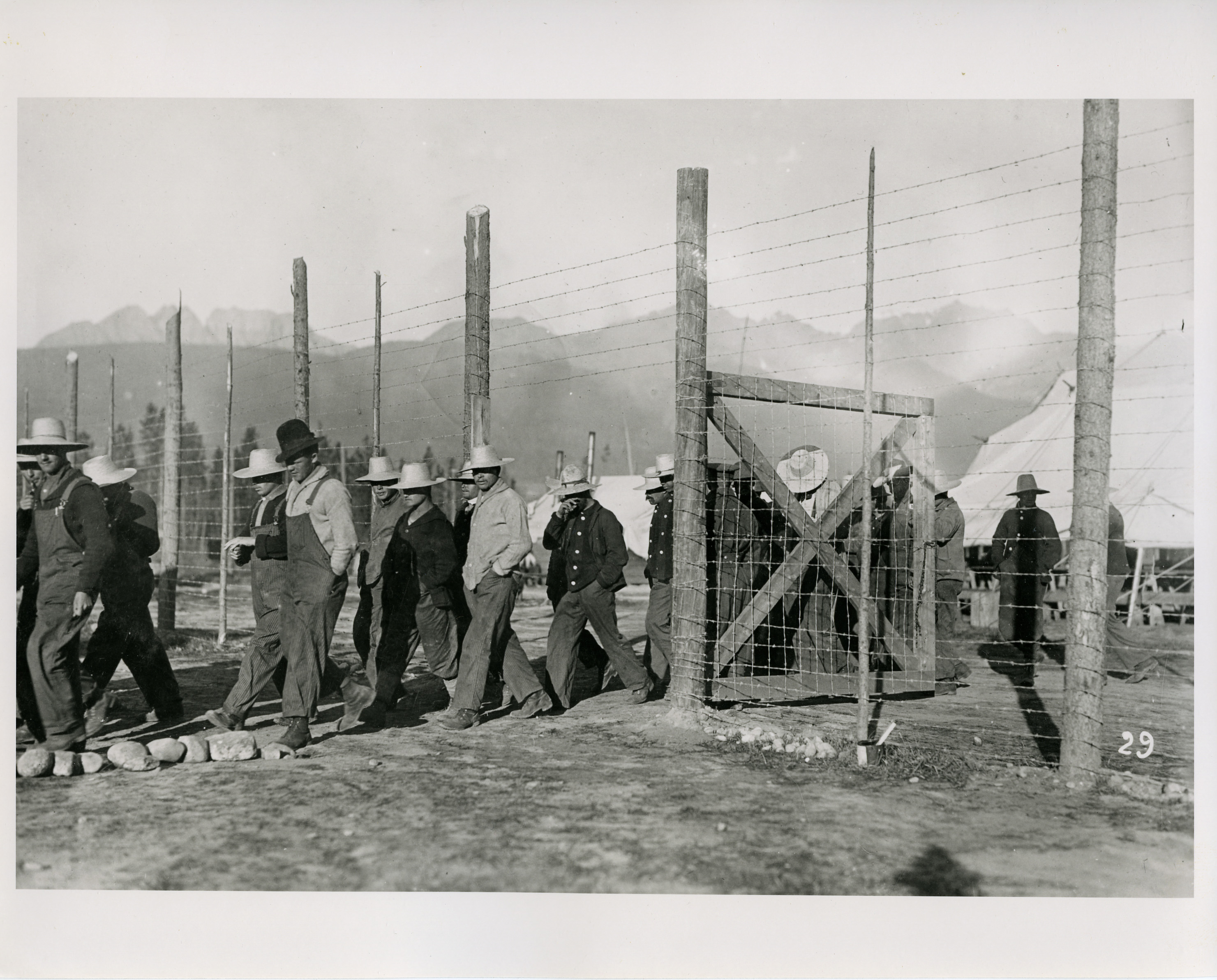

All interned enemy aliens were technically prisoners of war. But they were not treated the same. German nationals were kept separate from other groups and confined in such places as old Fort Henry in Kingston, Ontario. Ukrainians, on the other hand, were considered a labouring class and put to work at wood cutting camps in northern Ontario and Quebec or performed construction work in western Canada’s national parks. The majority of the park internees were stationed at Banff national park – alternating between a summer site near Castle Mountain and winter facilities at the Cave and Basin pool in the town site, while constructing a new road to Lake Louise. The Jasper internees devoted most of their energies to building a road to Maligne Lake. Similar work was performed at Mount Revelstoke. With the approach of winter, the men were transferred to Yoho, where they worked on a new highway and a bridge to the Kicking Horse River.

By the end of the first season, parks officials found the work to be satisfactory but complained about the slow pace and the almost constant supervision that the men required. One wonders, though, what more could have been accomplished since the internees were using only hand tools. They were also desperately unhappy. One Banff internee confided to his wife in a letter that they were “hungry as dogs.” Some quietly waited for the right moment and tried to escape even though guards were under orders to shoot. Relief seemed to be on its way in 1916. By the second year of the war, Canadian military commitments overseas had translated into a serious manpower shortage at home.

The federal government reasoned that the interned aliens might as well be released to fill wartime vacancies. Starting in April 1916, then, prisoners gradually began to be discharged to various companies. The Dominion Parks Service regretted the loss of the men because they tackled jobs that would have been otherwise impossible during the war. Those who had been interned, meanwhile, were confused and disappointed, if not bitter and angry, about their treatment. They had come to Canada for the promise of a better life. They had committed no crime–except for being from an enemy country. Nor were they found to be linked to any subversive activity. It was an experience that successive generations would never forget.

These materials were taken from the W.A. Waiser fonds, MG 192.