Search Great War Images from the U of S

University Women

The University’s women generally remained in Saskatoon during the war years. Only one female student ventured overseas as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse. Her name was Claire Rees and she subsequently became the only woman to be named on the memorial ribbons on the walls of the University’s College Building; one woman in the company of three-hundred and forty-nine men.

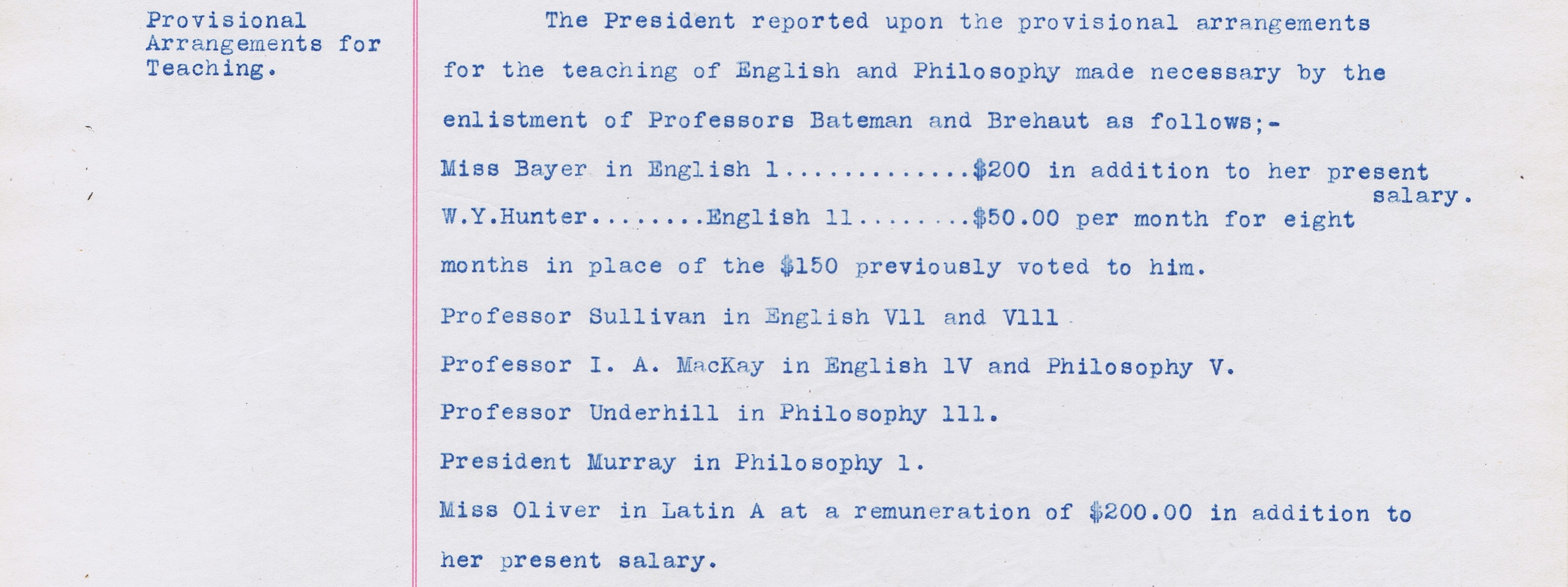

Although the women of the University of Saskatchewan – besides Rees – did not follow their male classmates to the European front, they were certainly involved in, and affected by, the Great War. Their world changed irrevocably throughout those pivotal four years. So too did their place in the university. As the numbers of male students and teaching staff were heavily depleted by the war, women’s roles on campus modified and their responsibilities increased. It was especially the case in the field of academic instruction (Lamb Drover 2009:69). When Professor Bateman vacated his post as English Professor partway through the school year, for example, Miss Jean Bayer filled the vacancy as instructor of English 1. Miss Bayer, who had held various posts prior to this appointment, continued teaching throughout the war and eventually went on to be named Assistant Professor of English, a rank rarely held by women in that period.

Besides taking on new positions, it is clear that the University’s women also strove to involve themselves in the war effort--to do their bit on the home front. Their endeavours to send parcels and provisions to their male counterparts reveal their need to do their part and care for their friends and brothers in peril. The soldiers’ appreciation for their efforts was considerable. For instance, letters to Mrs. Christina Murray laud the usefulness of the knitted socks sent by the University’s women. Likewise, correspondence between Dr. Murray and a female student discusses the practicalities of sending apples to the soldiers. Other letters from the men praise Murray, the University, and the women who helped organize Christmas parcels for the University’s fighting men.

The female students and staff members no doubt had a model to emulate, when it came to war-time behaviour, in the University President’s wife, Christina Murray. A staunch advocate of the University’s young fighting men and an active participant in various interested committees and councils, Mrs. Murray was drawn whole-heartedly into the war effort, much like her husband. In fact, in February of 1918 she was one of fifty Canadian women to attend the Women’s War Conference in Ottawa. Newspaper clippings which she kept on subjects--ranging from the conference itself, to food production, security and rationing measures to adequately supplying the men at arms, and increased female labour--reveal her deep concern with the role of the home front in this global crisis.

(Left:)Mrs. Christina Murray with her daughters: left to right, Christina, Lucy, Jean and Mrs. Murray. A-5642. The ferocity of the women’s support for the young fighting students, and the war effort in general, was not always expressed in positive form. It did not only manifest itself as knitted wears and Christmas parcels. Dr. Michael Hayden reported: “Some female students harassed those males who did not enlist, waving white feathers in their face and taunting them as cowards as they walked by.” (Hayden 2006:11).

(Left:)Mrs. Christina Murray with her daughters: left to right, Christina, Lucy, Jean and Mrs. Murray. A-5642. The ferocity of the women’s support for the young fighting students, and the war effort in general, was not always expressed in positive form. It did not only manifest itself as knitted wears and Christmas parcels. Dr. Michael Hayden reported: “Some female students harassed those males who did not enlist, waving white feathers in their face and taunting them as cowards as they walked by.” (Hayden 2006:11).

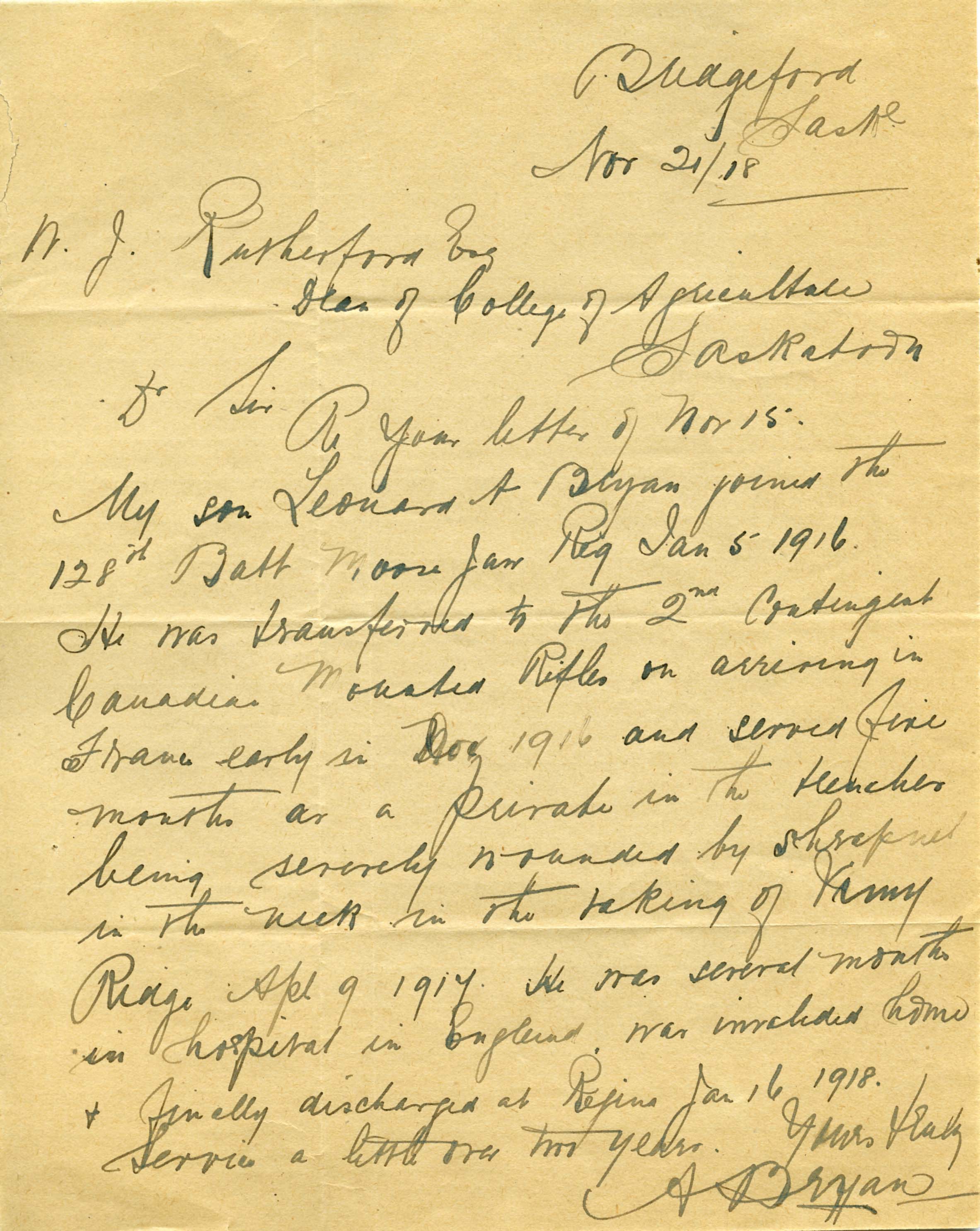

Through their actions, both positive and negative, wives, mothers, sisters, friends and classmates of the men at arms, the University’s women were far more than disinterested bystanders during the Great War. Their hearts were also laid bare on the battlefields of France. Letters from various parents to Dean Rutherford – which the Dean had sought in order to document the involvement of the University’s agricultural students in the struggle – provide a glimpse of that combination of anxiety and pride so characteristic of war-time mothers.

The University’s women were indelibly affected by the war. They stayed behind and saw the gender balance at the school shift to their advantage. Some took up new roles and responsibilities just as women throughout the province were donning jobs that had belonged to their husbands and sons. In the midst of coping with new work and responsibilities, shortages and rationing, they also showed their support by providing comforts for their fighting brethren.

Yet, it wasn’t really until the last year of the war that the University women had a chance to shoulder risk and direct their caring impulses to something more immediate and tangible. When peace was finally declared, a plague descended on the University in the form of the Spanish influenza pandemic. And in response, when the city took the step of turning Emmanuel College into an emergency hospital, a number of university women immediately volunteered to nurse the sick. They did so under the direction of Mrs. J.A. Macdonald, a nurse and wife of the school’s French Professor. Mrs. Murray, herself, offered her house up as a residence for these young women. Morton writes: “Conditions could not have been worse in the improvised hospital. Only the advanced, the hopeless cases were sent to Emmanuel. Sanitary conditions were most unsuitable for a hospital, and yet cleanliness was essential. Three male students volunteered to do the scrubbing; within three days, all fell ill and one died. Yet the girls continued their daily duty, in eight-hour periods, throughout the course of the scourge” (Morton 1959:109). For their effort, these women’s names were painted on their own section of wall in the College Building – above the stairway to the left of the entrance – not far from the banners naming their many class-mates and friends who had done their part in another type of fight.

The above material has been gathered from the Walter Murray President's records, the Jean Murray fonds, and the pamphlet collection